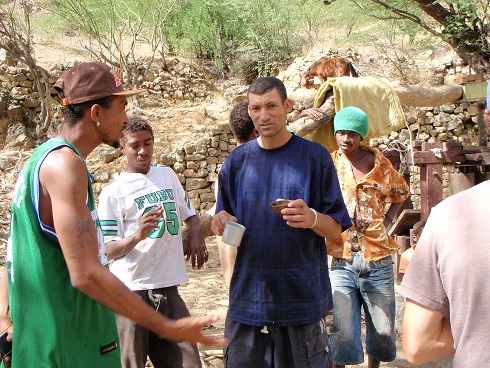

Vixen arrived in Barbados after a voyage of 18 days from the Cape Verde islands. This was our third Atlantic crossing and the boat's fourth. Before leaving we checked out of Cape Verde but then sailed to the next island down the chain – Brava – which is much less visited by yachts. We sailed overnight from the city of Praia and arrived the next day in a beautiful deep bay with a fishing camp on the beach and a village atop the surrounding cliffs. A young fisherman, Jose was our guide. He took us up to the poor little village which contained just the minimum to call it a village– a couple bars and a store that seemed to sell not much more than raman noodles and biscuits. It was Christmas day and Jose insisted I try the various rums made from the sugarcane in the fields around the village. In the Cape Verdian creole they call it “grog” which I guess must be a hold over from visiting sailors of another era. To return to Vixen we walked back through the cane fields. Soli requested some sugarcane for our trip and Jose hacked off a bundle of cane which we nibbled on all the way to Barbados. Deep in a valley below the village we came apon a grog still and an old cast iron sugar press. Here the grog sampling continued while I yammered away in Portuguese with the distillers. For me it was interesting to make comparisons between Cape Verde and the Azores: Similar food and Portuguese heritage but Cape Verde has a fascinating Brazilian and African influence. Both the Azores and Cape Verde have strong connections to the USA with emigrants sending back money to the poor island communities. At the bottom of the valley we could see Vixen but we couldn't get past the sheer cliffs to our dingy. No matter, Jose dove in and arrived a few minutes later with the dingy which he then jumped out of so we could get in and go back to Vixen. On the 26th we spent the day preparing Vixen and left in the evening for the 2,034 mile trip to Barbados. We had plenty of wind, from 10 to 30 knots the whole way. We hardly saw any other ships. It always amazes me how crowded we are on land but at sea we can sail for week after week without any sign of humans. The fishing was good: I landed several mahi mahi which bolstered our somewhat meager provisioning in Cape Verde and Senegal. The most exciting catch was a big mahi that vomited an eight inch flying fish down Vixen's companionway and onto Solianna's head as we brought it on board. Every morning I would clear the decks of flying fish which had flown aboard during the night. Sometimes I would eat one for breakfast. Tiffany and I settled into a new watch system of five hours on and five off during the night. I would have the 9pm to 2am watch and then Tiffany would take it to 7am. We both managed to read Dumas' 1,500 page Count of Monte Cristo on the night watches. I listened to my favorite podcast – The Thomas Jefferson Hour and perhaps a few too many Fresh Air radio programs -- I started to dream that the host, Terry Gross, was one of Vixen's crew. http://www.jeffersonhour.com/ When we finally sighted land on the 18th day Tiffany and I were ready to be ashore. We dreamed up increasingly fantastical mirages of what we would do – large salads and cold beers and toes in the white sand. The two girls, however, seemed happy to just carry on. Seffa really had little interest if we ever got to land. Until I mentioned ice cream – that got them going. The biggest problem on the voyage was that it appears we are ready for a new mainsail. It ripped during a jibe and we had to lower it for a couple of hours while I stitched and patched it. We were hoping it would get us home to the northwest but I think it has just seen one two many oceans. I feel lucky to be in Barbados because it is so hard to get here from the US and the rest of the Caribbean islands which lie downwind. This weekend is the Mount Gay Rum round the island race. First prize is the skipper's weight in rum. Gotta love the Caribbean!  One Month in Senegal and Hard Travel to Cape Verde Vixen arrived two days ago in Cape Verde on the island of Santiago. We have been sailing on the Casamance River in southern Senegal for the last three weeks. Ten or fifteen years ago this area was a favorite cruising ground for French yachts but times have changed (mainly due to new visa requirements). Unbelievably, Vixen and our friends on Vega had the whole Casamance basin – which runs 30 miles from the Atlantic Ocean entrance to the city of Ziguanchor, plus miles and miles of navigable backwaters – all to ourselves. So for three weeks we lazily drifted with the tides up and down the river deep into serpentine bayous visiting small African villages of a couple hundred to a couple of thousand people. The anchorages were great – 10 to 20 feet deep over sand with hurricane-hole protection among the mangroves. The bird life was spectacular: pelicans, hawks, herons, parrots and vultures. And lots of fish jumping in the river. One day we had the most enormous dolphins alongside while we motored downstream. They were the size of pilot whales. The villages are either Catholic, Muslim or animist or a combination of the three. Usually you can find a cold beer and sometimes an intermittent internet connection. Most villages have no cars or paved roads because they are on islands in the river. There are solar panels for basic electrical needs. The people here are Diola while those from the north are Wolof. Sometimes a Gambian will be visiting friends and speak some English but otherwise French is spoken everywhere. We were on the river during the rice harvest. In the morning the women of the village would paddle by Vixen on their way to the rice paddies. In the afternoon the dugouts would come back laden with rice. At the end of our stay we rode the tide eight miles up a side estuary from Karabane to Ehid. We had been told to stop at the thread-bare naval base at Elenkine to check in with the officials there. I obediently anchored then rowed ashore to talk to one of the officers. He seemed to appreciate the gesture and simply waved us on without looking at any papers. Elenkine is an interesting town because it is where the fishermen come to dry fish and truck it inland. For this reason there are lots of wooden pirogues in the anchorage and being built on the beach. The pirogues are big here – up to 60 feet long and carry some serious cargo. I watched one boat builder ripping a plank from an inch-and-a-half thick hardwood board that was about 15 feet long. There were actually two guys sawing away from either end with simple rip saws. I asked one of them in French how long it would take to cut one plank. “Oh, about five hours,” he said without much concern. The boats are roughly built but very distinctive with jutting stems, long graceful sheerlines and colorful paint jobs. There is almost no working sailing vessels in Senegal; they all seem to have large diesels – surprising when the price of diesel is about $2 a liter. Because the planks are so roughly fit together they fill the gaps with tar and then tack a piece of rubberized canvas over all the seams on the inside of the hull. We continued on to Ehid most of the time appearing to sail over dry land on my electronic chart. The river is basically uncharted as far as I can tell. Fortunately, a French sailor in Dakar had given me some waypoints taken during a previous visit that allowed us to avoid the sandbars. The village of Ehid is known as a sacred village and central to the animist culture. There are fetishes everywhere: pig's jaws or shells hanging from trees or clumps of knotted grass. They believe that these things are watching over them and they pray or ask favors of the fetishes. The village is built of mud-wall houses with tin roofs. There are large baobab trees and banyan trees that look to be hundreds of years old. People have marked off their little huts with sticks driven into the sand to form fences which line the footpaths. The center of every hut has a master's chamber and in this room is a pantry in which the family's rice is secured under lock and key. One night we joined a party on the beach around a bonfire. There was drumming and dancing and a pot of freshly fermented palm wine. The main food here is rice and fish but there are also oysters which grow on the mangroves. They chop off a mangrove root covered in oysters then throw it on the fire. In fifteen minutes you have smoked oysters on a stick! I asked someone about the sustainability of chopping the mangroves and was told that that only happens occasionally. Usually the oysters are scraped off the roots to preserve the mangroves. There is an understanding that the mangroves are necessary for juvenile fish to mature. In this rural environment, with almost no schedule, day after day seemed to slip by on Vixen. I started to sort out who was related to who in the village. We would see a friend we knew from one village at another further up the river. There seems to be lots of back and forth travel by pirogue. We gave away lots of kids clothes and stuff we didn't need on Vixen. Unfortunately, after one month our cruising permit was expired so we checked out and prepared for the 450 mile trip to Cape Verde. The Casamance river entrance is well marked but it has a few curves and would be difficult maneuver under sail alone. We picked our tide to ride out to the sea with the current. The final turn to the open ocean, however, turned against the tide and the prevailing winds and waves from the north. We had three miles to motor into ocean swells and about twenty knots of wind. Vixen crept forward. I started thinking about my Perkins engine and where any weakness might be found. To loose power at that moment would be a disaster. There wasn't room to sail upwind in the narrow channel with sandbars and breaking seas on either side. There was also no one to call for help on the radio. I hate to think what our fate would have been if the motor had quit at that moment. But the old Perkins chugged on and we reached the open sea. Finally we could fall off the wind and set sail. For the next 50 miles there were fishermen in open boats setting nets over the shallow bank off the coast of Senegal. I dodged them as best I could but sometimes in the darkness had to run between two flags marking a net. It reminded me of sailing in Indonesia where the only sign your about to run into a fishing boat is a frantic flashlight flicking up and down. The appropriate response seems to be to have your own flashlight and flick it up and down then turn to port or starboard and see if the flicking becomes more or less frantic. To get to Cape Verde we knew we would have the wind forward of the beam so it wasn't to be a downwind cakewalk. We were prepared, if the wind shifted west and strengthened, to skip Cape Verde and sail all the way across the Atlantic without stopping. For the first day we had the predicted 18 knots of wind from the northeast. Solianna and I sat in the cockpit and sucked on baobab seeds fresh from the tree. Then on our second day out I called a container ship that was on a collision course with us and asked if he would mind altering course to port to avoid Vixen. The captain politely agreed. Then ten minutes later he called us: “You are very brave,” he said in an eastern European accent. I thought about that for a minute and then called him back: “Ah... what do you mean we are very brave?” “Well. I've just looked at the 12 hour forecast and this swell is going to increase and the wind will get very strong. Very brave.” “Very brave or very stupid,” I thought to myself. There had been no indication of a coming gale on the weather information I had downloaded a day earlier. But sure enough that night, after Tiffany and I put a second reef in Vixen's main, the wind blew and mountainous waves pummeled Vixen. Normally, I would have hove-to in these conditions and waited it out but as I didn't know when the storm would abate I decided to try to reach the shelter of Cape Verde. After two days of getting hammered by the elements there was a lull and on the fourth day out we reached the harbor of Praia. We reached shelter just in time because the next day the wind and rain came on stronger than ever. The whole city of Praia was submerged in a torrent of brown water. Everybody said it was very unusual weather. Vixen was caked in salt water and the red dust of the Sahara desert born by the wind. I told Solianna and Seffa, “If you take a lick of that you can say you've eaten sand from the Sahara dessert.” Seffa looked hesitantly at Solianna to see if I was joking and then they both took a salty lick of the pin rail. On Vixen we were just happy to be safely anchored and not getting tossed around on the open ocean.  Anyone who has read Patrick O’Brian's Aubrey-Maturin series of sea novels knows the importance of having a generous reserve of Madeira wine stashed in the captain's quarters. Vixen is now well stocked in this regard: After a fast and rough sail from the Azores we dropped down 500 miles to the island of Madeira and its satellite, Porto Santo where Madeira wine is readily available. Sea captains have traditionally had a yen for Madeira because it keeps well in the warm agitated environment of a ship at sea. Apparently, it is possible today to buy drinkable bottles of Madeira which were produced before the American Revolution. Such endurance comes from a fortified alcohol level and a gentle heating of the wine before being bottled. The heat oxidizes the wine in a controlled environment and arrests any secondary fermentation in the bottle. This process – called estufagem – is essentially a mild form of pasteurization. Historically, Americans have loved the stuff – partly because the original 13 colonies produced no wine of their own and also because Madeira kept well in the southern colonies which had no properly cool wine cellars. This is the wine that toasted the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the inauguration of George Washington and the launching of the USS Constitution. Thomas Jefferson, markedly abstemious for a man of his time, had a weakness for a good Madeira. Other than the wine, we have enjoyed the long sandy beach of Porto Santo and the warm dry weather here at 33º north. We have caught up to summer again after feeling the first chilly nights in the Azores. Madeira is just 300 miles off the coast of Morocco – definitely back in the tropics! Before leaving for Madeira we spent about a week on the most southern Azorean island of Santa Maria. This little island is essentially a one village chunk of rock with a great harbor thanks to extensive man-made breakwaters. The village-- Vila do Porto – is the oldest in the Azores established in the 15th century. A lone Portuguese outpost in the Atlantic (50 miles downwind of São Miguel), Vila do Porto has been plagued by pirates throughout its existence. The pattern seems to have been this: A pirate or privateer would be cruising the Atlantic hoping to take a fat treasure ship on its way home from the New World. If this plan didn't play out then a back-up plan was to sack Vila do Porto just to cover the costs of the expedition. The ravaging of Santa Maria happened about once a decade for centuries. The most tragic part of the story, however, was not the burning of the town or the loss of the chapel's coffers but the capture of the citizens to be sold in the slave markets of Algeria. A plaque in Vila do Porto's town square states that in 1652 over 20,000 Europeans – including many Santa Marians – were kept as slaves in North Africa. It was such a problem that charities were organized in mainland Portugal to pay the ransom of the poorer citizens being held hostage. Vila do Porto sits atop a cliff a couple of hundred feet above the ocean. There are no trees in the surrounding dry hills and the island has a windswept forlorn feeling. There is a small fort looking over the harbor providing a clear view of the Atlantic to the south. The homes of the village are well shuttered and walled in. Despite this advantageous position there are stories of pirates anchoring in the night, scaling the cliffs and raping and pillaging before the inhabitants had a chance to flee to the hills. I can imagine the trepidation of the Santa Marians as a ship was spotted on the horizon – was it a much anticipated trading ship or pirate sizing up the town's defenses? At what point did the Santa Marians decide to leave their homes and run to the hills? Fortunately, our visit to Santa Maria was free of any of such decisions. Vixen's plan now is to continue sailing south to the Canaries.  Island of Pico Island of Pico The Fine Art of Wave Watching Vixen left Flores for an overnight trip to the central group of islands in the Azores, specifically to Horta Harbor – one of the main crossroads of the world for voyaging yachts. The wind forecast looked good – northwest 15-20 knots – for the 130 mile trip but I had a feeling the swell would be running high; all night Vixen had strained at her mooring lines from the waves entering the small harbor of Lajes das Flores. This feeling proved true as we got clear of the protection of the island; it was a nice sailing day but a two-meter swell was running at right angles to Vixen's course chucking her up and down. In addition, there were squalls, up to maybe 30 knots which had Tiffany and me striking the jib and putting a single reef in the mainsail. Often people ask me what I do day-to-day during an ocean passage. I usually have the feeling of having had a lot to do – of having been “busy” for the whole trip whether it be one day long or thirty. But, if you ask me what I did the whole time I have trouble answering specifically. On this last voyage from Maine I decided to consciously keep track of what I was doing from hour to hour. Apparently, I spend a lot of time looking at waves. You could call it “keeping watch” but, in fact, there were many times when I could have been down below or busy with some activity but instead I chose to spend hours looking at the waves. Watching waves is endlessly interesting to me. Although a wave's characteristics in a typical forecast might be reduced to “1.9 meters high from the northwest” in reality there are always mosaics of wave patterns overlayed on the ocean's surface. Usually I can pick out two or three wave patterns other than the prominent wind-driven swell. Traditional Polynesian navigators can pick out many more and will, in fact, triangulate a boat's position by keeping track of subtle wave patterns. Polynesian navigators have even proven that they can detect the reverberation of a wave pattern off of an island 50 or even 100 miles away. These reflective waves are clearly visible from aerial or satellite images but I have found them very difficult to sense from the deck of a boat. Only many decades of serious wave watching can fine tune this ability. Besides the information-rich patterns of the ocean's waves there is another element which makes for interesting wave watching: the capricious nature of the earth's winds. I can be sitting in Vixen's cockpit reading my book and look up to see waves of a certain tone, say, ominous or aggressive or lazy or gentle. I'll look down for five minutes to read and when I look up again the tone will have changed, often quite dramatically. I imagine this is because the wind – the wave's driver – is seldom perfectly constant. Just as a ferocious squall can come blowing through on an otherwise calm day I've see moments of slick calm for 5 or 10 minutes in the middle of a full gale. What causes these changes I can't say for sure. There must be upwellings and mid-oceanic currents and atmospheric pressure differentials that we can't see which make the ocean the dynamic and unpredictable environment that it is. On this last trip from Maine we had a few hours of absolute calm. There was still a slight heaving to the ocean's surface but no detectable wind. Even the lightest wisp of a telltale hung limply from the stays. Then I would just get a feeling that there was a breeze. Not a feeling like wind on my face because it was lighter that that but a feeling inside that there was some wind. I think it actually came from my eyes watching the waves; if I looked carefully at the glossy roll of the ocean I could see tiny fissures in its surface – tiny indentations along the backs of the swells. My mind was unconsciously registering this slight pattern as wind and if I focused and looked carefully at the little divots I could actually see from what direction the new wind was coming. And sure enough 5 or 10 minutes later the telltales would lift, a faint breeze would brush my cheek and the new wind would have arrived. An hour later Vixen would be doing 7 knots on a broad reach in a 15-knot southwest wind. My scariest times on Vixen have been when I haven't been able to see the surface of the waves. It is not unusual on an ocean passage to have nights of true darkness. Nights when you can hold your own hand inches from your face and see only blackness. These are nights with no moon and heavy cloud cover to obliterate any starlight. Sometimes a trickle of phosphorescence still streams off the rudder leaving an eerie luminous path. The most haunting experience for me is to be sitting in Vixen's cockpit and hear a large wave coming towards us – a big crasher thundering through the darkness. As it approaches I can hear that the sound is coming from above head level and for a moment I wonder if Vixen will rise to meet this rogue. Fortunately, Vixen always has lifted her buoyant stern but often not without me getting a full saltwater slap in the face. On the other hand, some of the most sublime moments on the ocean are in the early morning after a gale when the sea is running high. As the sun breaks above the horizon the low-angled light beams across the waves. If I'm lucky I'll sometimes see one wave cresting higher than the others and a then a blast of sunlight will go shooting through it. The wave's pewter-dull surface transforms, for an instant, into a brilliant translucent prism of turquoise, greens and blinding white froth. Vixen is now in Horta Harbor. We had a great week over on Pico watching the whaleboat races and staying in our friend Helen's traditional homes. At some point in the next month we will head south to the Canaries. |

AuthorBruce Halabisky is a wooden boat builder and sailor. He and Tiffany Loney are the owners of Vixen. Archives

January 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed